On January 10, 2024, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) published Guidelines, applicable to any technology, for ascertaining compliance with the enablement requirement in view of the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Amgen v. Sanofi (“Amgen”). According to the Guidelines, which will be incorporated into the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure in due course, the USPTO will continue to use the In re Wands (“Wands”) factors when determining whether claims in a patent application are enabled. The USPTO considers that its current policies on enablement are consistent with Amgen and post-Amgen enablement decisions from the Federal Circuit.

In Amgen, as previously discussed, the Supreme Court (“Court”) unanimously affirmed the Federal Circuit in answering the question of what is required to satisfy the enablement requirement for a patent claim directed to a functional genus. The Court held that Amgen’s patent claims1 directed to a genus of monoclonal antibodies that are functionally defined (i.e., antibodies that bind to specific amino acid residues of the PCSK9 protein and block the binding of PCSK9 to a LDL cholesterol receptor) lacked enablement. The Court held that, even though Amgen’s specification disclosed the amino acid sequences of 26 antibodies that perform the claimed functions, Amgen’s claims “sweep much broader than the exemplified 26 antibodies” and Amgen “failed to enable all that it claimed, even accounting for a reasonable degree of experimentation.”2

In the Guidelines, the USPTO provided the following analysis:

- In Amgen, the Court relied on precedent from a wide variety of technologies.3 Therefore, there is no reason to treat the Amgen decision as limited to antibodies or biotechnology. The principles set forth in the Amgen decision regarding the enablement requirement apply to all fields of technology.

- The Court emphasized that the specification may call for a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use the full scope of the claimed invention. That reasonableness standard is still the one to be applied following Amgen.

- In Amgen, the Court did not explicitly address the Wands factors. However, the Wands factors are probative of the essential inquiry in determining whether one must engage in more than a reasonable amount of experimentation. The Wands factors were applied or discussed in the Federal Circuit’s Amgen v. Sanofi decision, which the Court affirmed, and the post-Amgen Federal Circuit enablement decisions, Baxalta v. Genentech, Medytox v. Galderma, and In re Starrett.4

- Consistent with these Federal Circuit decisions, the Wands factors will continue to be used by the USPTO to assess whether the experimentation required by the specification to make and use the entire scope of the claimed invention is reasonable or undue. Federal Circuit precedent applying the Wands factors prior to Amgen is still informative as to how the Wands factors should be analyzed in different situations.

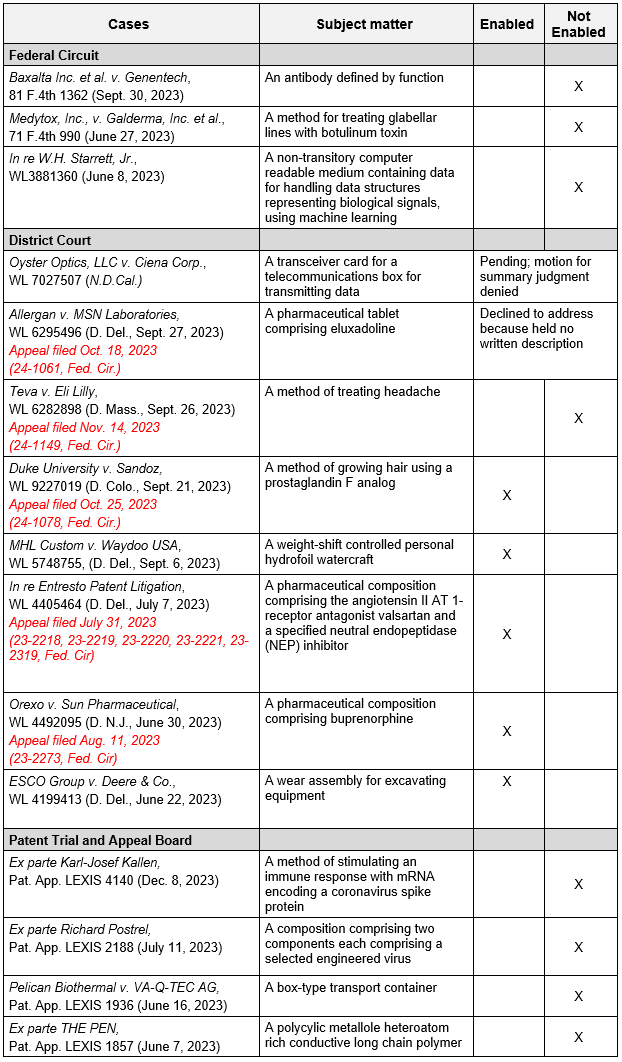

Notably, in all post-Amgen Federal Circuit cases, which are referenced in the Guidelines, along with all Patent Trials and Appeals Board (“PTAB”) cases citing Amgen, the genus claims at issue were found not enabled across various areas of technology. Post-Amgen district court decisions have been mixed, with some findings of enablement (by the jury) based upon the particular facts and generally narrow claims. At least five of the district court cases have been appealed to the Federal Circuit. A table of these post-Amgen cases is provided below.5

Because the Wands analysis is a multifactorial, fact specific analysis, it is challenging to make a generalized conclusion as to what is sufficient, enabling disclosure and what is not. Enablement guidance for a specific patent application continues to be drawn from analysis of enablement case law in the relevant area of technology. In technology areas where results are less predictable until reached, such as where simultaneous conception and reduction to practice occurs, less is enabled beyond the disclosed species. The Court considered antibody technology an unpredictable art, stating that “scientists cannot always accurately predict exactly how trading one amino acid for another will affect an antibody’s structure and function,” concluding that “[t]he more one claims, the more one must enable.”7

Because the Guidelines are essentially a review of current jurisprudence without any further guidance or examples, we will all need to stay tuned to witness – and to participate in – Amgen’s impact.

1 US Patent No. 8,829,165 (Amgen):

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody, wherein, when bound to PCSK9, the monoclonal antibody binds to at least one of the following residues: S153, I154, P155, R194, D238, A239, I369, S372, D374, C375, T377, C378, F379, V380, or S381 of SEQ ID NO:3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

US Patent No. 8,859,741 (Amgen):

1. An isolated monoclonal antibody that binds to PCSK9, wherein the isolated monoclonal antibody binds an epitope on PCSK9 comprising at least one of residues 237 or 238 of SEQ ID NO: 3, and wherein the monoclonal antibody blocks binding of PCSK9 to LDLR.

2 Amgen v. Sanofi, 598 U.S. 594, 613 (2023).

3 See, e.g., Holland Furniture Co. v. Perkins Glue Co., 277 U.S. 245 (1928) (related to a starch glue); The Incandescent Lamp Patent, 159 U.S. 465 (1895) (related to incandescent lamp); and O’Reilly v. Morse, 56 U.S. 62 (1854) (related to electro-galvanic force for telegraph).

4 2023 WL 3881360 (Fed. Cir. 2023) (non-precedential).

5 Post-Amgen Federal Circuit, District Court, and PTAB Enablement Cases

6 Amgen, 598 U.S. at 600.

7 Id. at 610.